If you are dealing with eighteenth or nineteenth century gentlemen´s fashions you will sooner or later come across discussions about a certain detail: the neckcloth, also known as the cravat or possibly the stock. What exactly did gentlemen wear around their necks?

Any chap during the Regency era would feel terribly undressed without the tall collars and the neckcloth. The contrast between starched white linen and a dark coat is striking. It frames the face in a flattering way. At the time one sought to create the illusion of one´s head resting nobly on a Grecian column. The greatest dandy of them all, Beau Brummel, is often given credit for the look. His doings have been described so often, so I will leave him at that.

Cravats are basically a length of fabric tied around the neck in a knot. But are the cravats triangular or rectangular? Exactly how stiff is it supposed to be? If I was planning to make a new cravat – should I look for bleached linen of finest possible quality or readily available cotton batiste? Or silk? What is historically accurate? There seems to be different opinions on that matter.

Perhaps I am a fool, but I decided to make an attempt to sort out the intricasies of the cravat, mainly through portraits and some extant examples, and I wrap it up with showing you a couple of basic knots.

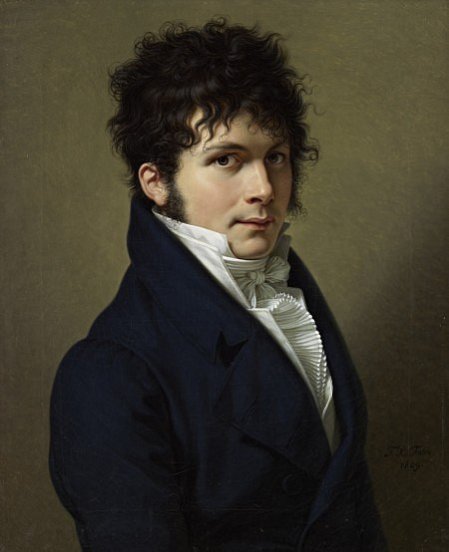

Let us begin with taking a look at some portraits:

Richard Cosway: Portrait miniature of a gentleman, “wearing blue coat with gold buttons, tied stock and frilled cravat”, 1790. The softer look of the Georgians is transforming into the high collar and stiff cravat of the Regency. Is he actually wearing a stock AND a cravat? I thought the frill came with the shirt…

A-L Girodet de Roucy-Trioson: Portrait of J. B. Belley (detail), deputy for Saint-Domingue, 1797. Musée National du Château, Versailles. A nonchalant cravat paired with a frilled shirt. The amount of fabric and the ends suggest that this is a square folded into a triangle.

Francisco de Goya: Portrait of Marques de San Adrian, 1804. Museo de Navarra. Large knot with the short ends pointing in different directions.

Jean-Francois Sablet: Self portrait, 1805. Collar, cravat (or stock), and frill. The knot is so small it nearly blends with the frill, so is Monsieur Sablet actually wearing a stock?

Francois Xavier-Fabre: A Young man, 1809. Scottish National Gallery. Similar style, but the overall effect is well-starched crispness.

M-J Blondel: Portrait of Pierre-Jean-George Cabanis, c. 1810. Frill is gone but the collar is higher than ever. Is this a stock, with the ends tied in front? It seems very stiff, yet loose fitting. Does the shape of the ends suggest a triangle shaped cravat? And the stiffness leads us to… starch.

Starch? Seems to have been essential, since it is so often mentioned. I wonder how stiff the cravats actually were though. They do not always look all that starched to me. (Just look at the Marques above.) Would it be possible to tie a neat bow if the fabric was stiff as paper? Or was it enough to starch only lightly just to keep the white crispness? (As opposed to labourers in soft neckcloths in different colours.) Or was it different depending on whether it was half dress or full dress? Anyway, rice starch would apparently do the trick – although I have not tried it yet. All that washing, starching, and ironing sure kept the maids busy. Especially if you discarded a neckcloth that didn´t turn out well. You only had the one chance.

Adventures with starch, an interesting discussion over on the Regency Society of America . (Image borrowed from there.) Note that the collar is made in two pieces: the upper piece is slightly gathered to a lower band. The frill is detachable. This image gives a good view of the equally starched cuffs.

Good example of collar and frill, on another shirt. (I am not sure this is an extant garment.) The collar was either left standing or was folded down over or under the tie. Borrowed this image from excellent Darcy clothing.

It is very similar to this shirt from Nordiska museet, Stockholm, that I had the opportunity to examine some time ago. It was obviously not starched at all, but of very fine quality. One difference is the closure with ties instead of buttons.

The neckcloth could be worn under or over the shirt collar. This is crucial for the result. During the eighteenth century before collars increased in height, they could be folded down before or after tying on the cravat. The collar would then be either completely hidden or visible like a modern shirt and tie combination. The overall narrower silhouette towards the end of the century saw the new fashion of keeping the collar upright with the cravat clearly visible.

Baron Gros: Baron Gerard. Ca 1790. The Metropolitan museum. A folded down collar. (The collar is actually very tall, since it is folded down and still touches the jaw!)

Thomas Lawrence: Portrait of Humphry Davy. Ca 1821. National Portrait Gallery, London. Only the very top of the collar is folded down over the cravat.

The often cited pamphlet Neckclothitania was published in 1818 as a satire that made fun of popular cravat styles of the time. The descriptions are written in a style that was entertaining but were probably not meant to be taken too seriously. They look like the same knots with very small variations.

The actual neckcloth was cut either as a rectangle or square. Sources differ, but there were basically three options when choosing the material: finest linen, cotton lawn, or silk, always white. Coloured neckcloths were introduced in the 1820´s, but the white neckcloth continued to be used on formal occasions, a custom that survives to this day. Shirts could be of a lesser quality since little of them actually showed, saving the finer material for collar and cuffs. I have always preferred the rectangular cravat, which in my opinion is easier to handle. Mine is about one foot (30 cm) wide and sixty inches (150 cm) long, hemmed and folded lengthwise along the middle. The ends are cut straight along the grain of the fabric and are consealed by the waistcoat. Another option is to cut them diagonally, which gives a nice finish when tying a knot with exposed ends. When the neckcloth is a square, about one yard on each side, it is first folded diagonally, then folded again and again until a suitable width.

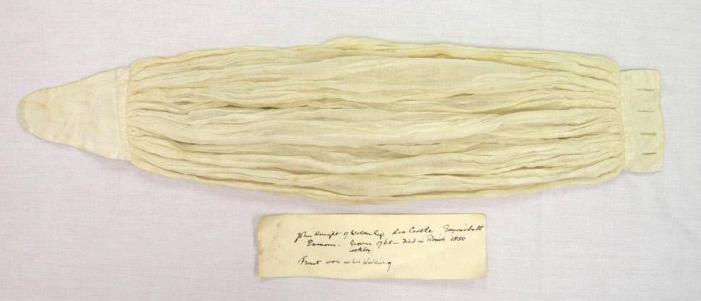

An alternative to the cravat was the neck-stock. This might come as a surprise to you. At least I have never given it much thought before. The stock is essentially a pre-tied cravat. This was the most formal neckwear, a collar or band of white material of a fine quality, carefully pleated horizontally to fit over a shirt collar and tightly around the neck. They could be without folds too, and were then stiffened with paper and sometimes even boned like stays. Military officers often wore black stocks, made of fabric or leather. The stock had tabs in the back that tied, buttoned or buckled together with a metal buckle. Buckles were commonly used because they were easier to adjust and they kept the stock firmly in place. During the eighteenth century the stock often had a decorative ruffle, jabot, gathered at the front. This is the cause of some confusion, I think. Another version (that still exists today) is the stock with hanging linen bands, known as short bands. These stocks represented the learned professions, clergymen, barristers, and academics. This looks very much like a cravat with the decorative ends hanging down, covering the shirt breast. Sometimes when a gentleman desired a nice knot or bow, a cravat was tied on top of the stock. I think they simply led a parallell existence. The stock was in use in civilian fashion through the 184os-1850s (and came in different colours), before shrinking into the narrow clip-on bow tie of the late Victorians.

Impressive black stock on Marshal Bernadotte of France, later king Karl Johan of Sweden. Ca 1805. Painting by Joseph Nicolas Jouy, after François-Joseph Kinson. (detail)

“This stock is beautifully constructed from a lavish amount of material–62 inches of fine semisheer cotton gathered into the three-inch wide linen tabs that fastened at the back of the neck.” Colonial Williamsburg, Acc. No. 2008-114

White linen neck stock consisting of fabric gathered at each end to linen tabs with fine cartridge pleating. One tab has a single buttonhole for receiving a removable stock buckle with a T-shaped chape. Colonial Williamsburg, Acc. No. 2011-2

Stock and a fancy buckle. Image from Nadelmaid.

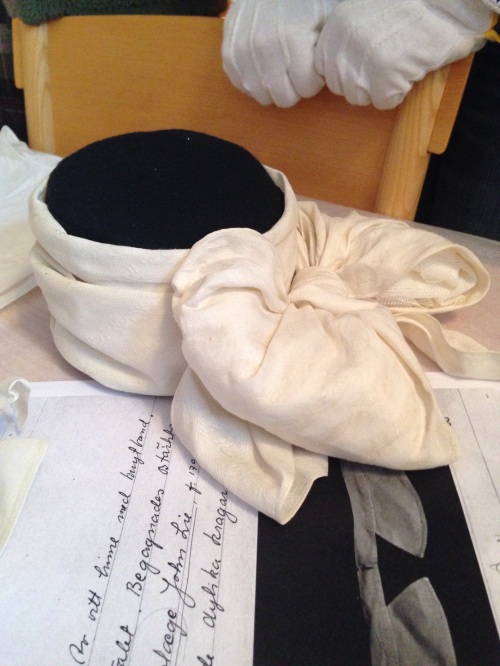

Elegant silk stock with the ends tied in a elaborate knot. Nordiska museet, Stockholm. 1820´s.

Neckcloth, in unstarched and badly tied condition. Nordiska museet, Stockholm. I photographed it, but failed to examine it more closely, so I cannot say if it is a stock or a neckcloth. At the time I thought a stock but now I think the latter. The image on the table shows an interesting detail: top collar sewn to a neckband. This would sit under the neckcloth with the ends showing under the chin. Is this the beginning of detachable collars?

No scroll back to the portraits, and do tell if the gentlemen are wearing a cravat or a stock!

I thought I would share my two favourite knots that even the beginner can master, considering that valets or personal servants are scarce in our day and age: The Mail Coach and The Barrel. They have been described many times. I borrow the following from Kristen Koster:

The Mail Coach or Waterfall Knot

This knot is simple enough to require no assistance in type, yet quite distinguished looking. The Mail Coach or Waterfall is made by tying the cravat with a single knot, and then bringing one of the ends over, so as to completely hide the knot, and spreading it out, and turning it down in the waistcoat.

1. Hold one end of the cloth in your right hand and the other in your left so the cloth is stretched out.

2. Find the midpoint of the cloth and place it at the front of your neck. Wrap the right side of the cloth behind your neck so the right end of the cloth comes out on the left side of your neck.

3. Wrap the left side of the cloth around the back side of your neck so that the end comes out on the front right side. Repeat if your cloth is long enough, layering the cravat so that it covers your entire neck. Leave at least a foot of slack on the ends of the cloth for tying.

4. Bring the ends of the cloth to the front. Place the left piece of cloth over the right piece of cloth to create an “X”. Pull the end of the top layer of cloth through the hole made at the top of the “X”.

5. Tighten the knot at the top of your neck. Arrange the top layer of cloth so that it covers the bottom layer and hides the knot. Spread the top layer of cloth so that it lies flat against your chest.

The Coachman or Waterfall Knot.

The Barrel Knot:

1. Repeat step 1-4 above. Make sure the ends are long enough.

2. Tighten the knot, and position it in the centre against the lower part of the cravat and collar. Now use the ends and tie another knot, and pull as tightly as desired. Arrange the ends down both sides of the shirt buttons.

My cravat tied in a basic knot, known as the “barrel knot”. I remember I was quite happy with the result.

A closeup of my basic knot. This one is not so tidy. The cravat is unstarched.

Conclusion: when looking at cravats and collars from the 1790´s to the 1810´s it is evident that they came in different shapes and used different techniques. Factors such as social status and place of geography propably made an impact, but I like to think that ones personal taste had a say in this,

So do not be afraid to experiment! I welcome comments if you have experienced the triangular cravat or tried the stock. Or starch!

Great article. I’m a member of a Regency dance group and attend a lot of balls and events in England. I need to make a new stock so have gained some new inspiration for a new shaped stock. Thank you.

That’s great! We don’t see them too often, do we? I’m making a very much needed stock the moment I have some spare time…

Hi! I loved this post! Such a good insight and so much interesting information. I was wondering if you possibly had any books and websites as to where you got all your info? I am doing a research project on cravats and am recreating one and would love to know more!

Thank you! I wrote this some time ago and don’t have access to all sources. I’m sorry I didn’t do my academic work properly! But I definitely used the V&A, The Met and Colonial Williamsburg collections database respectively, and I analysed the portraits (from public domain) that are included in the post.

I hope this was helpful enough…

No worries-your blog has already given me so much info! Thank you! I will have a good search through the museum data bases!

Pingback: New neckwear for the ball | Regencygentleman

Thankyou for your brilliant explanation. I make costume a d patterns and techniques are available from many sources for the ckstume maker. However once it is ‘over to you’ the wearer ,

giving an explanation about tying tbe stock and how they do it is ‘knot’ so easy. Until now I have made pre -tied stocks. I hope that I and my photography models can be a bit more adventurous now.

Many thanks for commenting! Sounds great and such a bonus that my blog could be helpful.

I only happened here by chance. Yesterday’s Guardian crossword referenced ‘stock’ in the wordplay to one of its clues and the blogger for fifteensquared.net (a site which critiques daily puzzles) offered a link to your dissertation. I noticed that it pleases you to receive comments. Although I’ve no particular interest in neckwear I have been impressed, entertained and enlightened (of course!) by your delightful article and wanted to let you know. Many thanks. W

Thank you kindly! Very much appreciated!

Alright! I am not well-versed in men’s fashion — past or present. I teach & study early American history & came upon your post after a quick search for “stock Vs. cravat.” Why? Good question! I have recently become interested in the “moderate” psychical appearance of Thomas Jefferson. Or, that his reputation of being practical and simple in dress, does not seem to match what is often described as his “lavish” lifestyle & spending. One source describing his fashion suggests that he combined elements from various eras (always practical), and wore buckled, “cambric stocks when cravats were universal.” Also, that he did not engage much in modern fashion & often preferred older, more practical styles. Now — did the cravat come before the stock? Or, as you said, did they, “led a parallel existence,” with either the stock or cravat becoming more fashionable at certain points in time? While they were both fashionable, that is…Perhaps it differs in early 19th century America. However, I assessment of Jefferson was made RE: his dress during or after his presidency — between 1800-1820 or so (died in 1826). Any insight?

If nothing else, thank you for the explanation! Most other sources speak of both pieces as if they were one…which caused me a lot of confusion! Certainly Jefferson would have been well aware of the distinction! He was..well, finicky and meticulous…. & not in a very appealing manner…:-|

Thank you!

I never thought I would have found such an article as this interesting. Thanks, must have taken quite the effort.

Good to hear! Thank you!

Hello,

I am late to your blog, but I have really enjoyed it, with all of those great examples, and the interesting comments that you have inspired. I feel obliged to add my comments, although I am not very qualified to speak up.

I have been working with reproduction nineteenth century civilian clothing for awhile, including some late 1840s gentlemen. So few of the young students who took on these roles could tie a very good knot in their silk cravats that I finally took pity on them, and had some stocks made up. We used the example in The Workwoman’s Guide, first published in 1838, plus an historic example of a shaped stock, dated 1842, made from figured silk that matched a vest, both apparently worn to the wearer’s wedding. One problem solved.

I can’t find my reference that said that the Prince Regent popularized the stock for civilian wear, and that it remained in fashion alongside the various cravats and neck cloths for several decades. Wearing a stock certainly improves your posture, and hauteur! The wearer looks down on pretty much everyone.

A clue to the demise of the stock would be to find out when it was discarded from the military uniform I would think.

While The Workwoman’s Guide was published later than your target, I still think that it has something to offer this discussion. In the Preface, the author says that “The patterns… have been some years in the collecting, and are given as the most generally approved shapes and sizes in present use.” In the introduction to dresses, we are told that some of the patterns are “independent of fashion” and aimed at servants and the poor. To me these statements indicate that some of the patterns are out-of-date, or favoured by the elderly. Possibly the stock patterns could be considered along with your extant examples to help construct a stock for your Regency costume.

I scanned the page, and the description, but I can’t get the scan to stick! Look for The Workwoman’s Guide, BY A LADY, A Guide to 19th Century Decorative Arts, Fashion and Practical Crafts, A Facsimile Reproduction of the original 1838 Edition, published by OPUS PUBLICATIONS, INC. AS this is the first time thatIi have found your blog, please forgive me if everyone is very familiar with this publication.

Sorry for my late reply, but thank you very much for your comment. Will check it out!

Pingback: Tying a Cravat… Let me Count the Ways | Austen Authors

Thank you for such an interesting blog, and great portraits and photos too. I can’t recommend highly enough the Regency novels of the incomparable Georgette Heyer. She is so witty and brilliant but above all historically accurate, in dress, manners and conversation. And men have always read her too (Stephen Fry a great fan). Her heroes spend hours on tying their neckcloths. The dandy or Corinthian (as she calls the dandy who are also an expert sportsman and horseman) is known to need hours in the morning tying the perfect cravat, with his valet patiently standing behind him with a series of carefully starched cloths over his arm, ready if the first attempts are not to his master’s liking. Enjoy!

Thank you for your nice comment!

Pingback: Neo Classic – Gunita’s blog

Excellent article! I am particularly honored that you referenced my trials and tribulations from the Regency Society of America! My cravats are starched enough to stand up on edge, but I’ve never found it difficult to tie the knot (I use the square folded into a triangle method, so the ends are much narrower). I’ve also found that a starched shirt collar and cuffs will stay crisp through several launderings.

Thanks so much for this- reading a primary source with a student in which a girl talks about making stocks to sell, and trying to describe what an early 19th-century’ stock’ was defeated me, so I found your blog and pictures- thank you again!

Pingback: Words in Progress: Percy’s Wedding Attire – EllieThomasRomance